The tragic death of 26-year-old Ifunanya Lucy Nwangene has thrust Nigeria's snakebite crisis into the national spotlight. The talented singer and architect, known for her appearance on season three of The Voice Nigeria and her work with the Amemuso Choir in Abuja, was bitten by a cobra while sleeping in her Lugbe apartment in the early hours of January 31, 2026.

Despite being rushed to the Federal Medical Centre (FMC) Jabi where she received resuscitation measures, oxygen, intravenous fluids, and polyvalent antivenom, Ifunanya died hours later from severe complications. The hospital reported she had arrived with advanced neurotoxic symptoms from the venom. Her death has sparked public outcry and renewed debate about access to effective, timely snakebite treatment in Nigeria, a crisis that claims thousands of lives each year, often far from the media's gaze.

"If Ifunanya died in the capital city, what hope is there for rural Nigerians?" observers have asked, highlighting the systemic challenges facing snakebite victims across the country.

A Doctor on the Frontlines

In the heart of Gombe State, Northeastern Nigeria, Dr. Nicholas Amani Hamman arrives at work each day knowing that lives hang in the balance. As Chief Medical Officer at the Snakebite Treatment and Research Hospital (SBTRH) in Kaltungo, he oversees the largest snakebite treatment facility in Sub-Saharan Africa, a hospital that has become a beacon of hope for more than 2,500 snakebite victims each year.

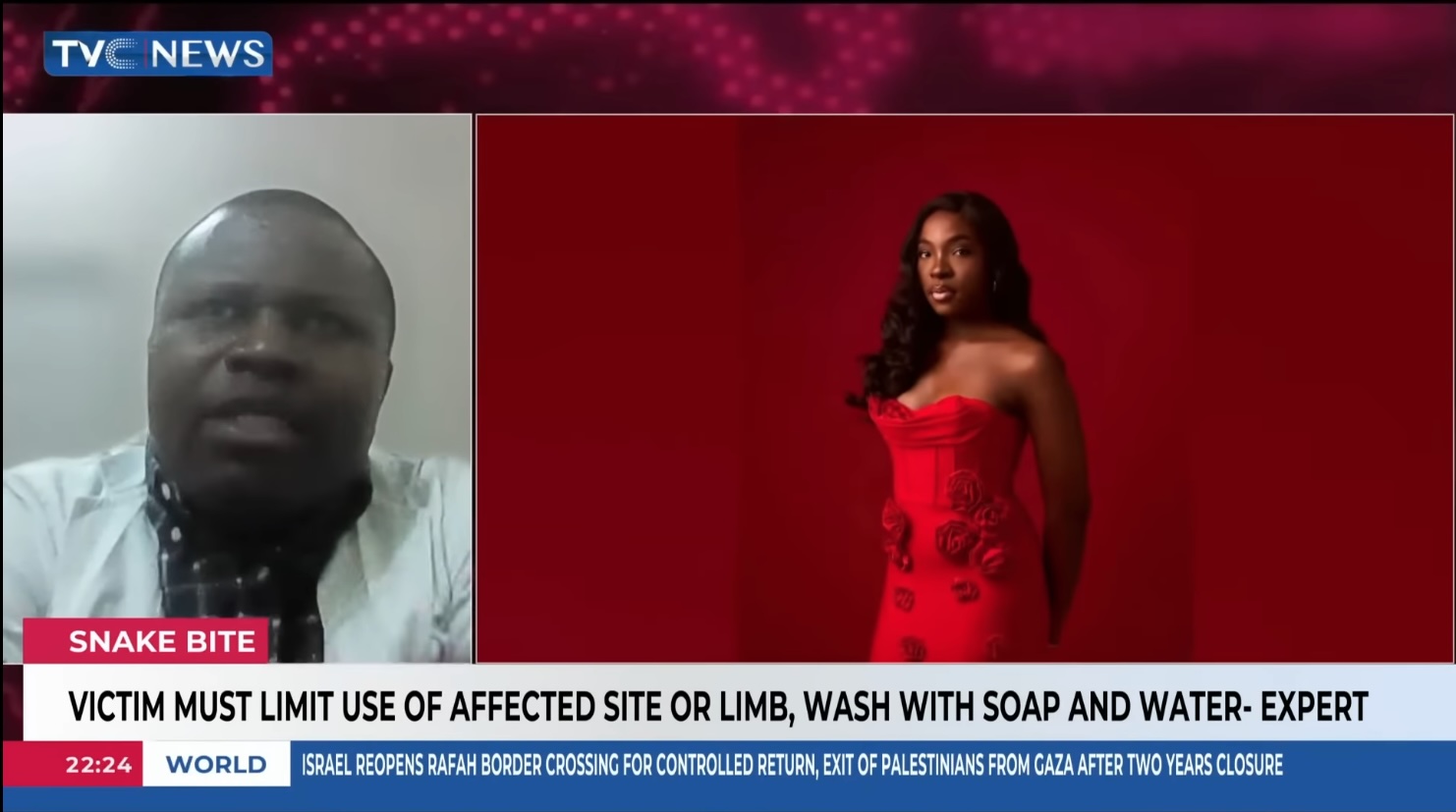

Dr. Amani's work goes far beyond emergency treatment. Under his leadership, SBTRH has transformed into a pioneering research centre, meticulously documenting every case to better understand how communities can be protected from this often-overlooked threat. His dedication to solving this public health challenge recently brought him to the national spotlight, where he was invited to share his expertise in the Nigerian media, helping to raise awareness about a crisis that has remained in the shadows for far too long.

Understanding the Scale of the Challenge

The numbers tell a sobering story. Nigeria's Federal Ministry of Health reports approximately 15,000 to 20,000 snakebite incidents annually, with roughly 2,000 deaths each year. Recent assessments by toxicology experts suggest the figures may be even higher, around 43,000 snakebite cases and approximately 1,900 deaths per year.

Yet these statistics likely represent only a fraction of the true burden. Many victims in rural communities never reach hospitals, instead dying at home or seeking traditional care that goes unrecorded in official health systems. Experts emphasise that the commonly cited figure of 2,000 deaths should be viewed as a conservative minimum rather than a definitive count.

"Hospital-based surveillance misses many cases," explains Dr. Amani, whose frontline experience has given him unique insight into the gaps in Nigeria's healthcare response. "We see patients who have travelled for hours, sometimes days, to reach us. For every person who makes it to our doors, we know others don't."

Ifunanya's case underscores a critical reality: even in Nigeria's capital city, with relatively quick access to a major medical facility, snakebite can be fatal. Her death has raised difficult questions about the availability of specialised antivenoms, the training of medical personnel in snakebite management, and the overall preparedness of Nigeria's healthcare system to handle these emergencies.

A Path Forward: Practical Solutions to Save Lives

Rather than dwelling on the problem, Dr. Amani and his colleagues at SBTRH are focused on solutions. Their meticulous record-keeping serves a vital purpose: identifying what works and what doesn't in the fight against snakebite envenoming.

Several key measures could dramatically reduce deaths and suffering:

Improved Access to Species-Specific Antivenom: While polyvalent antivenom exists, ensuring that the right antivenom for specific snake species reaches medical facilities quickly is crucial. Cobra bites, like the one that killed Ifunanya, require neurotoxic antivenom administered as early as possible. Currently, many facilities lack adequate supplies or the specific formulations needed, and victims can deteriorate rapidly while waiting for treatment.

Rapid Response Protocols: Time is critical in snakebite cases. Developing clear protocols for emergency responders, ambulance services, and emergency departments can ensure that patients receive life-saving interventions within the critical window when treatment is most effective.

Community Education Programs: Teaching people to recognise venomous snakes, understand first aid measures, and know when to seek immediate medical care can save crucial time. Simple interventions, such as avoiding traditional tourniquet methods that can worsen tissue damage, make a significant difference in outcomes. Urban residents, like Ifunanya, may be particularly unaware of snakebite risks and proper response measures.

Enhanced Surveillance Systems: Better data collection would help health authorities understand where snakebites are most common, which species are responsible, and how resources can be most effectively deployed. Dr. Amani's work at SBTRH demonstrates how systematic documentation can illuminate patterns and guide intervention strategies.

Training Healthcare Workers: Equipping medical personnel across Nigeria with proper knowledge about snakebite management—including recognition of neurotoxic symptoms, appropriate antivenom selection, and supportive care measures- ensures that patients receive appropriate care even at facilities that rarely see snakebite cases.

Research and Innovation: SBTRH's commitment to studying snakebite envenoming in the Nigerian context helps develop region-specific protocols and treatments, moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches that may not address local needs or the specific snake species found in different parts of the country.

A Model for Progress

What makes Dr. Amani's work particularly significant is its dual focus on immediate care and long-term solutions. Every patient treated becomes part of a growing body of knowledge that can help future victims, not just in Nigeria, but across Sub-Saharan Africa, where snakebite envenoming remains a neglected tropical disease.

The World Health Organisation has recognised snakebite as a critical health priority, and facilities like SBTRH demonstrate what's possible when expertise, commitment, and resources come together. Dr. Amani's research-driven approach shows that with proper investment and coordination, Nigeria can dramatically reduce the toll of this preventable tragedy.

Cases like Ifunanya's serve as painful reminders of what's at stake. A young woman with extraordinary talent, described by friends and colleagues as humble, intelligent, and exceptionally gifted, lost her life to a preventable cause. Sam C. Ezugwu, music director and co-founder of the Amemuso Choir, described her as "a rising star whose voice and spirit would be deeply missed." Her death has galvanised public attention on an issue that affects thousands of Nigerian families each year, most of whom suffer in silence.

Raising Awareness, Saving Lives

By sharing his expertise through media platforms and continuing his groundbreaking work in Kaltungo, Dr Amani is helping to shed light on a crisis that has affected Nigerian communities for generations. His message is clear: snakebite deaths are preventable, and with the right measures in place, thousands of lives can be saved.

Ifunanya's tragic death need not be in vain. It can catalyse change, spurring investment in antivenom supplies, training programs for healthcare workers, public awareness campaigns, and the research needed to develop better treatments and prevention strategies.

To hear Dr. Nicholas Amani Hamman's full insights on Nigeria's snakebite crisis and the solutions being implemented at the Snakebite Treatment and Research Hospital, watch his expert interview here: https://youtu.be/orRgc-h3cCw?si=C3EZ9DQbOkeUxAs1

Read more about snakebite research by The Global Health Network: https://globalsnakebiteresearch.tghn.org

Please Sign in (or Register) to view further.